Study for the Colonna Pietà (c. 1538), Michelangelo (1475–1564).

This study of the Pietà, drawn by Michelangelo in 1538, is small in size but monumental in significance. On both a personal and a theological level, it marks a major breakthrough for the sixty-three-year-old artist. Personally, it embodies Michelangelo’s gratitude toward a woman he had recently met, Vittoria Colonna. The widow of a general and a deeply religious woman, Colonna was one of Italy’s most admired poets. She became a kind of mother to Michelangelo, who had suffered throughout his life from the loss of his biological mother at the age of six. Their meeting led to a profound awakening for the artist: a new understanding of the Virgin Mary’s spiritual motherhood.

Mother and Child

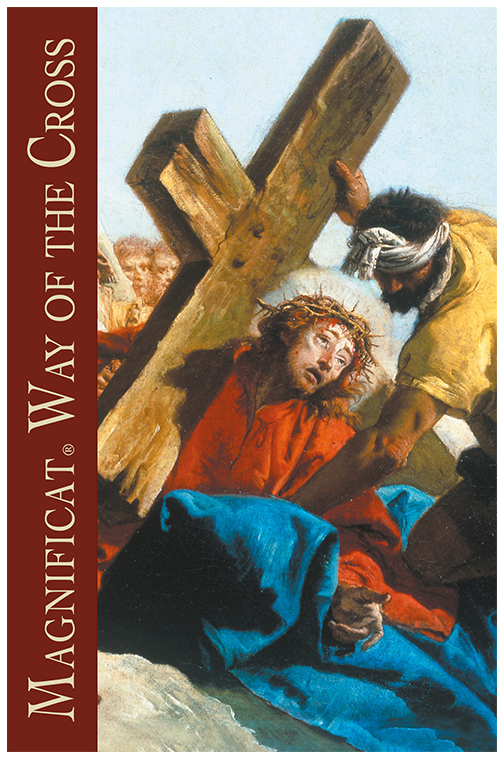

There is no question that Michelangelo displayed unmatched skill across numerous disciplines—drawing, painting, sculpture, architecture, and poetry. There was one theme, however, which he struggled to depict throughout his life: the relationship between Jesus and his Mother. In many of his paintings and sculptures—such as his 1504–1506 Madonna and Child or the strained depiction of Jesus and Mary in the Last Judgment—their relationship appears somewhat cold. Michelangelo even attempted to destroy the Florence Pietà, perhaps because he was unsatisfied with its depiction of the relationship between Mother and Son. The early death of his mother may partly explain this difficulty, but there is more to it. Michelangelo was also grappling artistically with the theological virus infecting the Body of Christ—the Protestant ideology. The issue was the definition of the Church as the Body of Christ, and since Mary is both the Mother and the archetypical member of this divine body, she finds herself at the center of the crisis.

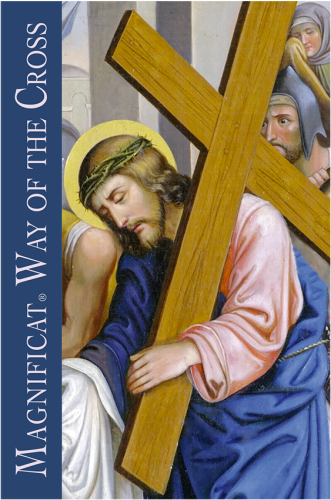

The Colonna Pietà is one of the rare instances in which Michelangelo successfully articulates the relationship between Mary and Jesus (an even more miraculous example being the Rondanini Pietà, which he worked on right up to his death). This drawing we have is a cropped version of the original, which included the horizontal beam of the cross in the upper portion of the composition. Mary sits at the foot of the cross, her eyes and arms raised toward heaven in a gesture of supplication and offering. The lifeless body of Jesus rests between her legs, supported on either side by two assisting angels. His face is downcast, and his arms hang limply, his fingers pointing downward in a subtle indication of his descent into hell. As in the two previously mentioned examples, Mother and Son look in opposite directions, and the body language does not immediately convey love or communion. Yet there is a deeper layer of meaning in this composition.

The unusual positioning of Christ’s body—his back turned toward his Mother, his arms resting on her legs—mirrors a traditional depiction of the crucifixion known as “the Throne of Mercy,” in which the dead Christ is shown resting on the Father’s legs, while the Holy Spirit hovers between or above them. In a bold move, Michelangelo substitutes the Mother for the Father. Moreover, the girdle tied around Mary’s waist mimics the shape of a dove hovering between them. In the Colonna Pietà, Michelangelo makes a profound theological statement about the relationship between Jesus and his Mother: Through the Holy Spirit, their union reflects the lifegiving relationships within the Most Holy Trinity.

Throne of Mercy

Inscribed on the vertical beam of the cross are Beatrice’s words from Dante’s Paradiso (Canto 29): Non vi si pensa quanto sangue costa (“They know not how much blood it cost”). In sonnets he wrote around this period, the aging artist often compared himself to Dante, “lost, in the midway of life,” entangled in the thorns of his own ego. In Vittoria Colonna, to whom he dedicated several poems, Michelangelo recognized his Beatrice: God’s chosen instrument to guide and support him toward the eternal source of all beauty.

Father Paul Anel

Pastor of Saint Paul and Saint Agnes in the diocese of Brooklyn, New York.

Additional art commentaries