Join the Great Prayer of the Church

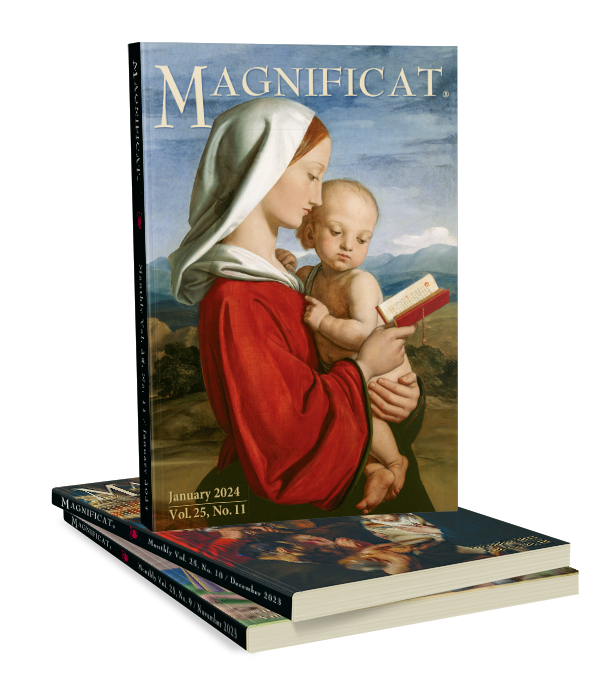

Magnificat is a monthly publication designed for daily use that aligns your personal prayer life with the liturgical rhythm of the Church, while immersing you in ongoing Faith formation.

GOSPEL OF THE DAY

A reading from the holy Gospel according to Matthew 25:31-46

Saint Who?

Join the Great Prayer of the Church

Magnificat is a monthly publication designed for daily use, to encourage both liturgical and personal prayer. It can be used to follow daily Mass and can also be read at home or wherever you find yourself for personal or family prayer.

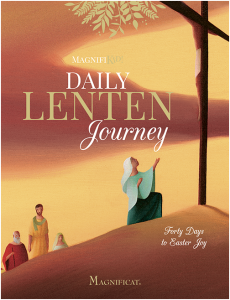

Forty Days to Easter Joy

Daily Lenten Journey

Embark on a prayer journey to draw closer to the Lord and make room in your heart for Easter joy!

$14.99 – Ages 7 and up -160p – 6.75 x 8.75 in.

THIS MONTH

February 2026

The cover of the month

The art essay of the month

NEW from MAGNIFICAT

Magnifier

Awakening wonder in every child!

A new bi-monthly magazine to introduce the marvels of the world to young readers ages 7-12

6 issue per year filled with exciting discoveries – $29 per year

Visit our

TO GO FURTHER

Magnificat Prayer Corner

Learn more

Prayer Corner

Praying to God - Prayers to Mary - With Saints - Every day - Church Prayers

By Fr Peter John Cameron, o.p: 40 short essays to nourish your meditation

Pray

Lenten Companion 2026

Come back to the Lord with all your heart.

A Companion for the Forty Days of Lent (from Ash Wednesday to Easter Sunday)

96 pages – 4.5 x 6.75 in. -$4.99 – Bulk prices as low as $0.99 for 1000ex

READ

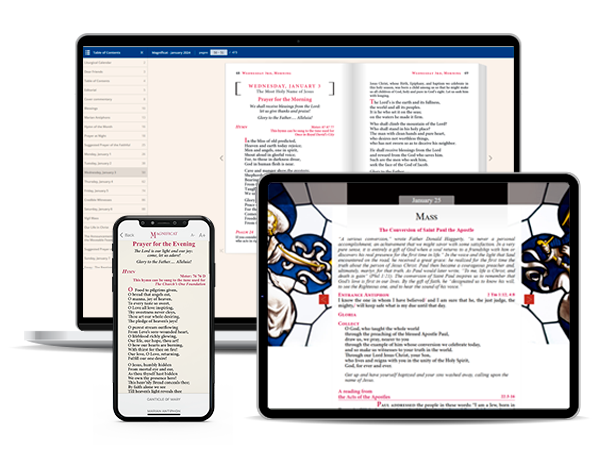

Magnificat Online and on your devices

Request sample copies

Take the time to discover Magnificat. Give your prayer life the beauty it deserves and share it with others.

NOTRE PROPOSITIONS DU MOIS

9 jours avec Saint Joseph

Chaque jour, laissons-nous guider par saint Joseph dans tous les aspects de notre vie !

Chaque matin, plongez au cœur de la lettre apostalique Patris corde.

Chaque soir, prenez le temps de méditer.

MAGNIFICAT

At Your Service

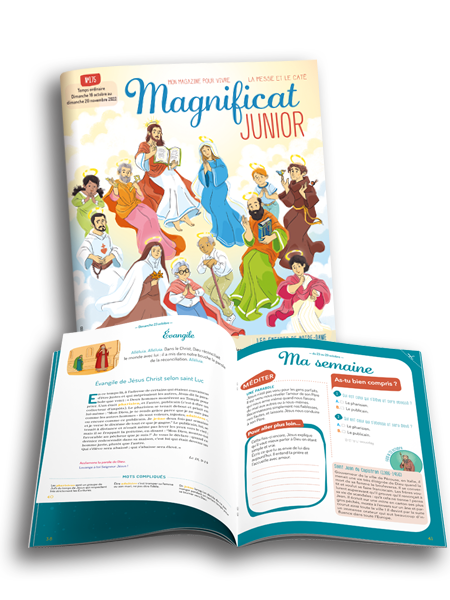

Help Children Pray and Follow Sunday Mass

An ideal spiritual guide for your children

Subscribers receive the issues on a monthly basis. In each month’s packet, children will find a booklet of sixteen color pages for each Sunday, and also special issues for the major feast days (Christmas, Ash Wednesday, Holy Week, Ascension, Assumption, All Saints Day).

Discover

Pour que la messe et la prière soient au cœur de la vie de chaque enfant !