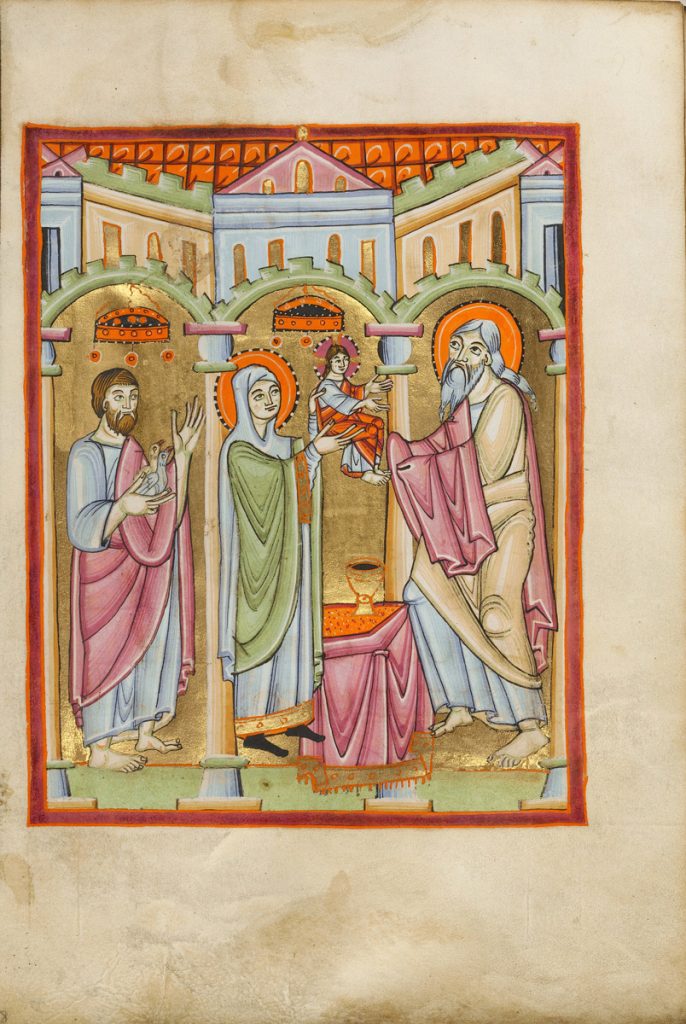

Presentation in the Temple (c. 1030–1040), Anonymous (Regensburg).

Poreč, a Croatian town across the Adriatic Sea from Venice, boasts one of the best-preserved cathedrals in the world. The Basilica of the Assumption of Mary, also known as the Euphrasian Basilica, was built by Bishop Euphrasius in the mid-6th century above an earlier church building. In addition to its octagonal baptistry, recalling the Resurrection of Jesus on the Eighth Day, the basilica boasts resplendent gold mosaics, including a depiction of Bishop Euphrasius holding a model of the church he built.

On the other side of the world, on a hill overlooking Venice Beach, a liturgical book once used at the Euphrasian Basilica is now preserved at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. Like the basilica, the Engilmar Benedictional is named for the bishop who commissioned it. A native of Bavaria, Engilmar served as bishop of Poreč in the mid-11th century. Engilmar’s Benedictional was produced in Regensburg, southern Germany, where Engilmar had likely lived as a Benedictine monk before becoming a bishop. Like the mosaic of Bishop Euphrasius holding his church, the opening page of the manuscript shows Bishop Engilmar blessing his flock with the aid of the Benedictional itself.

In the leaf of the manuscript shown here, another form of benediction is taking place. As the Gospel of Luke relates, when the parents brought in the child Jesus to perform the custom of the law in regard to him, [Simeon] took him into his arms and blessed God (Lk 2:27-28). Forty days after the birth of Jesus, Joseph and Mary have come to the Temple in Jerusalem to present him to the Lord. On the far left, Joseph clutches a pair of turtledoves or two young pigeons, the offerings specified in the Book of Leviticus for those who could not afford a lamb (Lk 2:24; cf. Lv 12:8). Mary, for her part, seems to have found a little lamb who is delighted to be offered. The baby Jesus reaches out with joy to Simeon, whose upturned face evokes his devout trust in the Lord. As we gaze at these serene figures, we can almost hear the echoes of Simeon’s Canticle of Praise: Now, Master, you may let your servant go in peace, according to your word, for my eyes have seen your salvation, which you prepared in sight of all the peoples, a light for revelation to the Gentiles, and glory for your people Israel (Lk 2:29-32).

The Regensburg illuminator saturates the scene with rich liturgical imagery. Mary elevates the baby Jesus above an altar on which rests a golden chalice brimming with dark red wine. While Simeon’s cloak serves as a sort of sindon or humeral veil to humbly embrace the Lord, Mary is privileged to touch Christ directly with her bare hands. These details give an unmistakably Eucharistic dimension to the painting, foreshadowing the sacrificial offering of Christ on the cross and the liturgical commemoration of that sacrifice in the Eucharistic liturgy. The Light from Light allows himself not only to be seen but to be touched, and indeed tasted. What was from the beginning, what we have heard, what we have seen with our eyes, what we looked upon and touched with our hands concerns the Word of life (1 Jn 1:1).

The Engilmar Benedictional was not made just to be looked at, but to be used. On the back side of the image of the Presentation in the Temple, a prayer of blessing is provided that Engilmar himself would have pronounced over his people each year on February 2. Like the solemn blessings used in the liturgy today on major feast days, this blessing has a threefold structure modeled on the priestly blessing in Numbers 6:24-26: The Lord bless you and keep you! The Lord let his face shine upon you, and be gracious to you! The Lord look upon you kindly and give you peace!

In addition to imitating the threefold blessing of Numbers, the three parts of this blessing especially emphasize the three persons of the Trinity. In the first part, Engilmar linked the Father’s sending of the Son to the ongoing blessings God provides through the Church: “May the Almighty God, who willed his only-begotten Son to be presented in the temple today in the flesh he had assumed, cause you who are supported by the gift of his blessing to be adorned with good works.” In the second part, Engilmar prayed that the Son’s example might not be a dead letter but a life-giving source of instruction: “May he who willed him to be a servant of the Law that he might fulfill the Law instruct your minds by the spiritual examples of his law.” In the final section, Engilmar invited the faithful to join themselves to the offering commemorated in the liturgical feast so that the Holy Spirit might dwell ever more richly in their hearts: “May you be able to offer to him gifts of chastity or charity in place of turtledoves, and may you be abundant in the gifts of the Holy Spirit in place of pigeons. Amen.”

Saint Leo the Great once preached that since Christ’s Ascension into heaven, “our Redeemer’s visible presence has passed into the sacraments.” When we gather for Mass, the mysteries of Christ’s life, death, Resurrection, and Ascension are made present to us—including the mystery of his Presentation in the Temple. It is Christ himself who speaks to us in the Scriptures and offers himself through the ministry of the priest. As Engilmar’s blessing reminds us, we are not meant to be passive observers, but active participants in the mysteries of Christ. As the Church teaches, all the faithful are called to offer themselves along with the Eucharistic sacrifice: “Taking part in the Eucharistic sacrifice, which is the source and summit of the whole Christian life, they offer the Divine Victim to God, and offer themselves along with it” (Lumen Gentium 11).

On the cross, the Lord Jesus has offered the one perfect sacrifice once for all. In his Presentation in the Temple, he gives us a foretaste of this oblation. May we in turn offer him gifts of chastity or charity in place of turtledoves, and in place of pigeons be abundant in the gifts of the Holy Spirit.

Father Innocent Smith, O.P.

Dominican friar of the Province of Saint Joseph and professor at the University of Notre Dame.

He is the author of Bible Missals and the Medieval Dominican Liturgy.

Additional art commentaries