Join the Great Prayer of the Church

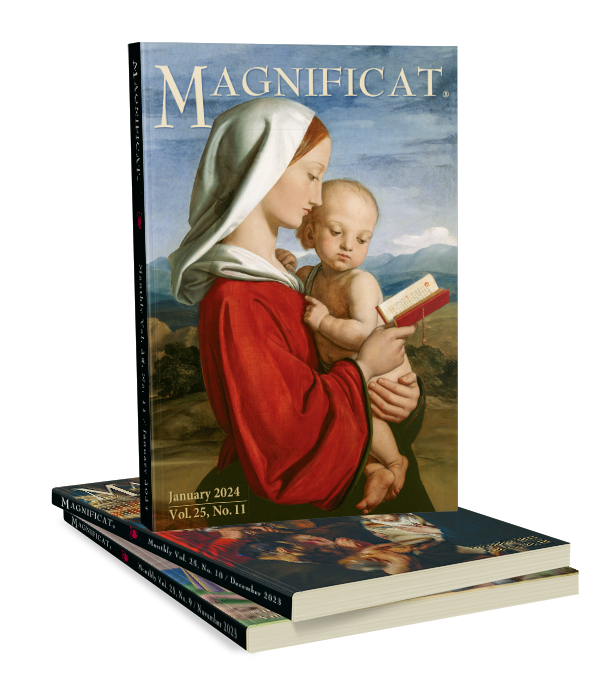

Magnificat is a monthly publication designed for daily use that aligns your personal prayer life with the liturgical rhythm of the Church, while immersing you in ongoing Faith formation.

A reading from the holy Gospel according to John 14:7-14

Join the Great Prayer of the Church

Magnificat is a monthly publication designed for daily use, to encourage both liturgical and personal prayer. It can be used to follow daily Mass and can also be read at home or wherever you find yourself for personal or family prayer.

MAGNIFICAT

Rosary for a Eucharistic Revival

With Mary, draw closer to her Son as you ponder these mysteries.

48 pages – 4,5 x 6.75 in. – $5.99 – as low as $1.99 for 500 copies

THIS MONTH

April 2024

The cover of the month

The art essay of the month

Visit our

TO GO FURTHER

Magnificat Prayer Corner

Learn more

Prayer Corner

Praying to God - Prayers to Mary - With Saints - Every day - Church Prayers

By Fr Peter John Cameron, o.p: 40 short essays to nourish your meditation

READ

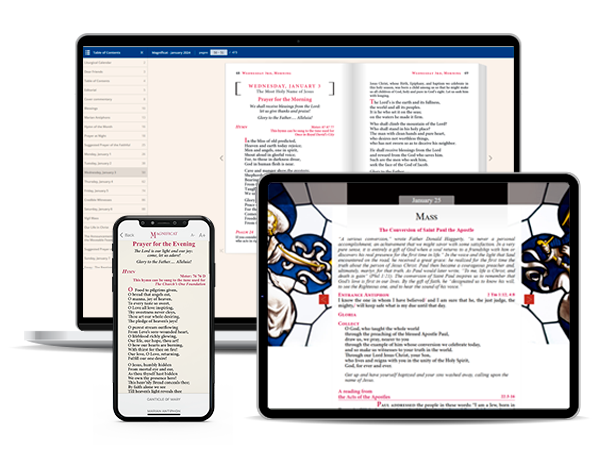

Magnificat Online and on your devices

NOTRE PROPOSITIONS DU MOIS

9 jours avec Saint Joseph

Chaque jour, laissons-nous guider par saint Joseph dans tous les aspects de notre vie !

Chaque matin, plongez au cœur de la lettre apostalique Patris corde.

Chaque soir, prenez le temps de méditer.

MAGNIFICAT

Request sample copies

Take the time to discover Magnificat. Give your prayer life the beauty it deserves and share it with others.

MAGNIFICAT

At Your Service

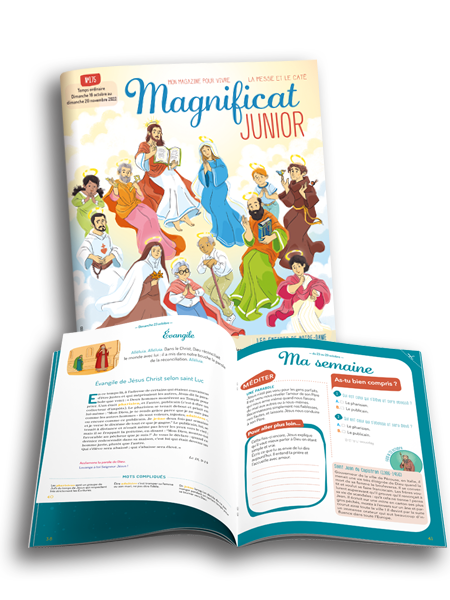

Help Children Pray and Follow Sunday Mass

An ideal spiritual guide for your children

Subscribers receive the issues on a monthly basis. In each month’s packet, children will find a booklet of sixteen color pages for each Sunday, and also special issues for the major feast days (Christmas, Ash Wednesday, Holy Week, Ascension, Assumption, All Saints Day).

Discover

Pour que la messe et la prière soient au cœur de la vie de chaque enfant !