Saint Luke (c. 1625), Valentin de Boulogne (1591–1632).

“The most Italian of the French imitators of Caravaggio”

At the heart of the royal apartment and in the center of the marble court in the Palace of Versailles, the “salon where the king dresses” received at the time of its creation, in 1684, nine pictures testifying to Louis XIV’s taste for Caravaggesque painting, all of them in the attic: works by Valentin de Boulogne, Nicolas Tournier (1590–1638), Alessandro Turchi (1578–1649), and Giovanni Lanfranco (1582–1647). When the room was turned into a bedroom, in 1701, only the four evangelists, The Tribute to Caesar by Valentin de Boulogne, and Hagar and the Angel by Giovanni Lanfranco were preserved in their original place. Saint Matthew, Saint Luke, Saint John, and Saint Mark, which today are still displayed in the same place, make up a cohesive ensemble. The Saint Luke was formerly placed opposite the Saint John and faced the Saint Mark, on the north wall, thus ensuring a chromatic continuity, which was modified in 1948–1949 when a new arrangement paired the Saint Matthew with the Saint Luke.

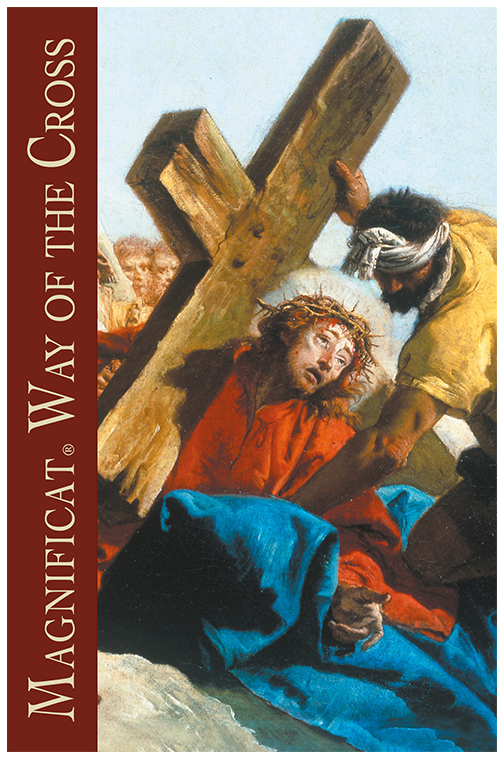

In the Saint Luke, Valentin de Boulogne, “the most Italian of the French Caravaggesques,” to quote the art historian Béatrice Sarrazin, demonstrates his debt to Caravaggio (1571–1610) as well as his personal language “marked by seriousness and melancholy.” Born in Coulommiers, the painter had no doubt arrived in Rome by 1609. With Nicolas Régnier (1588–1667), he met regularly with the Bent, a secret society of Transalpine artists, the Bentvueghels or “band of birds,” who were under the patronage of Bacchus, the god of wine. They liked to depict the lowlife of Rome, the Rome “of vice and poverty,” scenes in the taverns and the suburbs, and they developed an often irreverent and satirical art combining eroticism and morality. Valentin mixed also with other French artists, particularly Simon Vouet (1590–1649), who played a decisive role in the renewal of French painting. After his early years of production, dominated by genre scenes, Valentin became interested in religious painting.

The landscape-format compositions of Valentin de Boulogne’s four evangelists are balanced by an interplay of corresponding features. The series is based on a uniform pattern: each evangelist, together with his attribute, is depicted against a neutral, somber background, seated at a table, as though he had been caught while writing his Gospel. Reduced to its essentials, the iconography allows the spectator’s glance to concentrate on the personality of the evangelists, and it “masterfully expresses the divine inspiration.”

Luke’s gentleness

No doubt gentleness is what characterizes Luke, who is depicted with the ox that is traditionally associated with him. On the table he is busy writing at, the viewer notices a Virgin with Child. This little picture recalls that, according to tradition, Luke was the first to produce an icon of the Blessed Virgin, thus becoming the patron saint of painters. Valentin de Boulogne chooses to paint him as a young man, absorbed in writing his Gospel, holding the ink pot firmly in his left hand and the pen in his right hand. The wise use of chiaroscuro and of a range of colors—subtle tonalities rediscovered during a recent restoration—concentrates attention on the expression of his face, on his hands, and on the manuscript. We know little about Saint Luke, who was said to be a Greek, born, according to Saint Eusebius, in Antioch in Syria; the Letter to the Colossians (4:14) mentions him as a “beloved physician.” This “beloved physician” wrote one of the four Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles, having followed all things diligently from the beginning (Lk 1:3), and was a companion of Saint Paul, who accompanied him to Rome. A remarkable storyteller, Luke manifests in a particular way God’s tenderness and mercy: he is the only one to record, for example, the parables of the Good Samaritan and the Prodigal Son, the meeting of Jesus and Zacchaeus, the dialogue between Jesus and the good thief (Dismas)—memorable passages that plunge us into the heart of God’s infinite love. “Scribe of the gentleness of Christ,” according to Dante, Luke enables us to fathom God’s love for wayward humanity, wounded by sin. A historian, intent on giving an accurate account of the events that he relates to Theophilus—in other words, to all the “friends of God”—an instructor who hopes that his reader may know the truth concerning the things of which you have been informed (Lk 1:4), Luke is also a theologian who marvels at the divine mercy and brings to light, in a particular way, the role of the Holy Spirit who is at work from the beginning, both in the life of Christ and in that of the first Christian communities.

Valentin de Boulogne depicts this patron saint of painters and physicians deeply absorbed in writing his Gospel, his face marked with gentleness. May the contemplation of this picture encourage us to immerse ourselves in Luke’s inspired writings, so as to marvel at God’s action in our lives and at his infinite mercy.

Sophie Mouquin

Lecturer in art history at the University of Lille, France.

She is a frequent contributor to the French edition of Magnificat.

Additional art commentaries