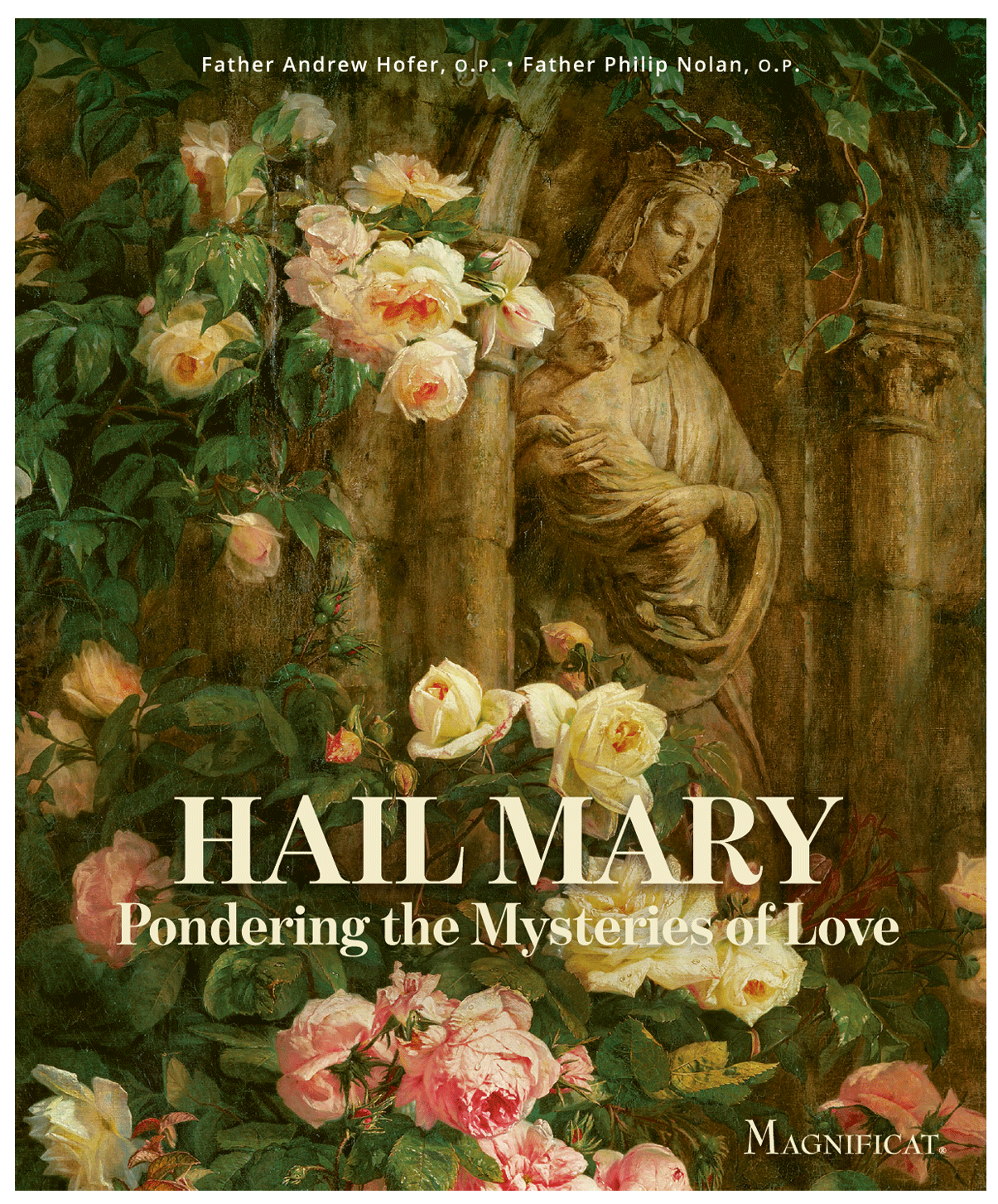

The Virgin of the Rosary (1650–1655),

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617–1682).

The most striking particularity of this 1650 painting by Murillo is the naturalness of the composition. Mary holds her naked child standing on her lap, their cheeks tenderly caressing. Mary’s composure is quiet, confident; she looks at us straight in the eyes. There is no secret message in that gaze, whether joyous or foreboding, nothing that would need decoding. She has the transparency, the clarity of innocence. And Jesus looks just like his Mother, and also like any well-fed, well-loved one-year-old boy. His left hand rests on her bare flesh, by the shoulder. Hers rests on his back, securing the child who is at that age when he is not yet strong enough to stand without careful oversight. Nothing is contrived or ostentatious in their demeanor. If it were not for the rosary, nothing would distinguish them from any mother and child from 17th-century Spain.

The naturalness of the Virgin

This raises a serious question, one that challenges the legitimacy of Christian iconography but also the very essence of our faith in the Incarnation. Before we get to that, let us clarify our observation. The composition is “natural” in three different ways. First, the Virgin herself is natural. She is looking in our direction, or rather, in the painter’s direction, as if she had come to his studio in Seville and posed, with her child, for the painting. We know her to be the Immaculate Conception, the New Eve, the Queen of Heaven, but nothing in her attitude shows the slightest self-awareness, and certainly not the all-too-conspicuous false modesty of someone trying to hide her importance.

A Child like any other child?

That Mary should be thoroughly natural seems only fitting. Isn’t she, after all, the humble “handmaid of the Lord”? What is otherwise surprising is that she makes no effort to emphasize the identity of her son. She did not even bother dressing him for the occasion! In many such representations, Mary would dress Jesus as royalty and hold him with affected reverence, lest the viewer might fail, out of sheer ignorance, to show due respect to her divine Child. Maybe Jesus would even hold a globe or a scepter, something to unmistakenly point to his divine nature and mission. In this painting, Mary makes no such provision. She seems absolutely unconcerned by the fact that we may mistake him for a “normal” child, with nothing special about him—and if her tender and protective embrace declares him special, it is in exactly the same way that every child is special and unique in his mother’s eyes.

Now what of Murillo? He too makes no attempt to emphasize the divinity of his subject. Yes, he gives the child a rosary to play with, and he makes sure its cross falls in that little dark spot filling the hollow space between their bodies, so it would be more visible and symbolically shine as a light in the darkness. But is that enough? Holding a rosary does not identify the pair as Mary and Jesus as much as an anonymous Christian mother and child, since the rosary was introduced in the 12th century by Saint Dominic. The most astonishing omission is that Murillo did not paint the conventional halos over their heads. A few decades earlier, Caravaggio may have had a prostitute pose for his Madonna of Loreto, but he did crown the painted figure with a golden halo, to preempt any quid-pro-quo. Murillo, like Mary herself, shows no such concern.

Iconoclasm and the “peril”

of the Incarnation

In the 8th century, iconoclasm spread from the belief that the representation of Jesus led necessarily to the erroneous belief that Jesus is only human. Iconoclasts advocated for the banning of iconography in favor of the word, seen as more nuanced and holistic. When Murillo painted, in the 17th century, this old fear of images had found a new vigor in the Reformation, which would be better called a deformation, since its defense of the divinity of Christ relied on a systematic defiance of his Incarnation. Religion became a way to protect us from the peril of the Incarnation. The baroque excesses of the early Counter-Reformation defied its conclusions, but often while accepting its principles: eyes rolling up to heaven, ethereal bodies, Saints and Madonnas floating among the clouds… The flesh in perpetual ecstasy is under the constant and sometimes violent, upward pull of the spirit—as if, to honor the divine, one had to keep the human in check.

There is no such theological torment in Murillo. Not only is he not afraid of the Incarnation, but he wants us to embrace its beauty—because Mary embraced it, Christ embraced it, the Father embraced it. When Jesus came back to Nazareth, those who knew him as a child were dumbfounded: Is he not the son of Joseph? They lived across the street from the Son of God and the Immaculate Conception, and never noticed anything extraordinary about him, or her. As far as they could see, they were perfectly human, perfectly natural. And indeed they were. Jesus’ divinity is not to be found above or beside his humanity, but within it. God revealed himself, not through his word only, but also through the silence of his gaze, as Murillo so poignantly understood. His infinite love for us finds a human translation in the tender contact of his flesh with the flesh of his mother, the New Eve, and in the dark, hollow space between their bodies, where the cross shines as the ultimate act of their mutual love and obedience to the Father. And through the beads of the rosary, we too get pulled into that mystery and become a link of that great, redeeming chain of love.

Father Paul Anel

Pastor of Saint Paul and Saint Agnes in the diocese of Brooklyn, New York.

The Virgin of the Rosary (1650–1655), Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617–1682), Prado Museum, Madrid. © Photo Josse / Bridgeman Images.

Additional art commentaries