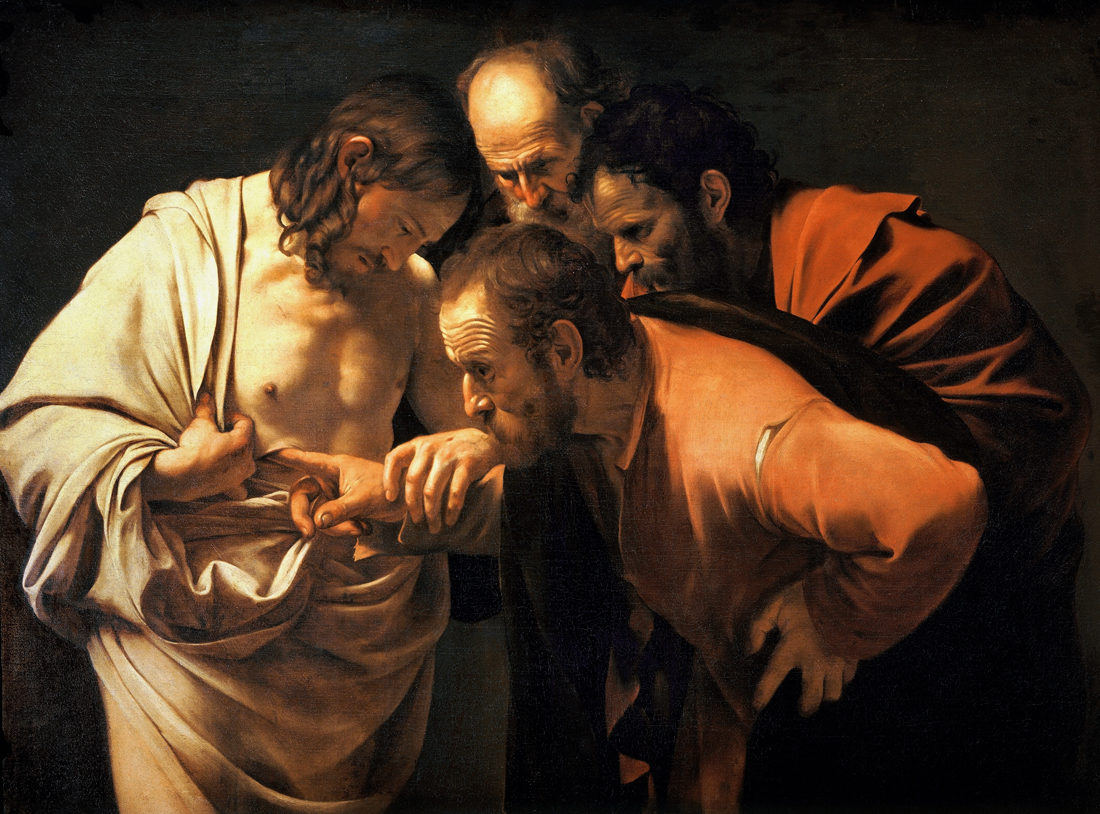

The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (1601–1602), Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610).

Caravaggio’s Incredulity of Saint Thomas was meant to make us uncomfortable. We are interrupting a private moment, and there seems to be no way to gracefully escape. Perhaps we could hide unnoticed amid the shadows, but Caravaggio’s tight composition with few participants would immediately reveal our intrusion. There is nothing to do but join this intent company. The four heads form a cross, recalling that a little over a week earlier, Jesus was crucified, died, and was buried. Yet the tall, luminous figure of Christ draws us to him together with Thomas, Peter, and John. Still wrapped in what looks like his shroud, Jesus is bathed in light pouring over him from an unseen source above. The chiaroscuro technique accentuates the human flesh over bone and muscle, a very real body. We follow the gaze of the apostles to the core of the composition, where Thomas’ finger is probing the wound in Christ’s side. Our instinct is to recoil. The dirty finger of this unkempt man is lifting the flesh around the laceration. The tear in Thomas’ shirt mirrors the wound, recalling the spear that ripped through Christ’s side at the crucifixion. Graphic and disturbing, yet it’s impossible to look away.

Daring patrons

Caravaggio’s startling composition came out of left field. Roman art did not have much of a tradition in the subject, although there was an altarpiece by Domenico Passignano in Saint Peter’s Basilica. By contrast, several artists in Venice and Florence had explored the theme, as did numerous manuscript illustrators. Some artists focused solely on Christ and Thomas, as in Verrocchio’s beautiful bronze statue group outside Florence’s Orsanmichele, where Jesus appears recessed in the niche, more distant from the viewer as Thomas approaches. Others depicted the complement of apostles giving Thomas a wide berth, as in Duccio’s Maestà. Albrecht Dürer’s engraving showed Thomas’ hand inserted into Christ’s side, heralding Caravaggio’s version, but the Milanese painter went further, appearing to open a gaping wound in space to suck us into this drama.

The work is believed to have been commissioned by Vincenzo Giustiniani, a wealthy Genovese banker, who with his brother Cardinal Benedetto Giustiniani was among Caravaggio’s greatest supporters and was instrumental in helping him obtain major public commissions. The brothers were deeply immersed in the Counter-Reformation culture of the age, actively promoting art as a compelling means to transmit truths of the faith. Caravaggio’s aggressive style of juxtaposing hyper-realistic details with supernatural light, disregarding perspectival depth in favor of figures jutting towards the viewer, and of leaving blank pictorial spaces to be filled by the beholder, appealed to these avant-garde collectors who were attempting to rekindle faith through art. Caravaggio’s Incredulity was so popular that many copies were made of the work, at least one by the master himself for an equally prestigious patron.

Our twin

Caravaggio’s innovative vision of Saint Thomas addressed head-on one of the greatest challenges of the 17th century: doubt. Of course, doubt was never alien to Christianity, but the Protestant Reformation and the printing press offered believers a multiplicity of new teachings, while the Age of Discovery encouraged people to place their trust in the empirical rather than the divine. Sacraments, especially the Eucharist, were questioned, and scepticism clouded belief. Patrons like the Giustiniani appreciated Caravaggio’s fearlessness in confronting these controversies through his art. Looking at this work, we can see that Caravaggio left a seemingly blank space between the bodies of Christ and Thomas, directly in our path as we approach the work. This space invites us to join Thomas Didymus, our “twin,” with all our doubts and questions. We look at his astounded face: he has seen and he has believed. Above, the apostles join us in our wonder; do we really believe that when Jesus was showing his wounds to Thomas the others remained aloof? We all want to see, to touch, to know, and the Church understands that. As Benedict XVI wrote, “Faith can only mature by suffering anew, at every stage in life, the oppression and the power of unbelief.” The cure for this doubt is humility, represented by the apostles with their somewhat dull expressions and tattered clothes, an interesting mirror for the urbane, elegant Giustiniani who would have stood before the work.

Once we have found our place in the painting, and accepted our own doubt and desire, we are ready to look up towards the shadowed face of Christ. His hand guides Thomas to the truth, his gentle expression revealing the love he has for us even in our own wounded, conflicted state. At this point, Caravaggio has drawn us so deeply into the scene that there is nowhere for us to go and nothing for us to say, except to echo Saint Thomas: “My Lord and my God.”

Elizabeth Lev

Writer and professor of art history in Rome.

Additional art commentaries