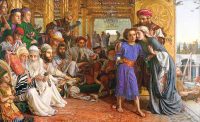

The Finding of the Savior in the Temple,

William Holman Hunt (1827–1910).

A visual vocabulary

In his Finding of the Savior in the Temple, William Holman Hunt presents the single moment between Christ’s birth and baptism captured by Scripture. Having reached the age at which young Jewish boys apprentice to their

fathers, Christ attends to his Father’s business (cf. Lk 2:49); he slips away from his parents and converses with the sages in the Temple.

Hunt engages the viewer in a quest to discover and decipher various clues throughout the painting. He weaves together a visual vocabulary of symbolism and allusion in a stunning panoply of textures, hues, and detail. Once recognized and understood, this artistic lexicon preaches an eloquent sermon on the trajectory of Christ’s life and mission.

A dramatic scene

Hunt was committed to archeological and ethnographic realism. He traveled to Jerusalem in order to research and paint on site, spending

several months studying the architecture and ritual of Second Temple Judaism before putting brush to canvas. Once sufficiently steeped in the subject, Hunt sought out Jewish models from among the poor of the city to sit for the painting.

An unfortunate clash with the local rabbinate stymied the artist’s progress for over a year. A European emissary named Albert Cohn alerted religious authorities to Hunt’s inquiries, resulting in a ban on Jews posing for the artist. Cohn then convinced potential sitters that the painting was destined to be worshiped in a church—for Jews, a flagrant violation of the commandments.

While this conflict was ultimately resolved, Hunt’s experience securing models transformed the tone of the piece. Preliminary sketches reveal Hunt’s original focus on a poignant reunion of the Holy Family. These compositional studies reflect the Scriptural source, which highlights the familial exchange and strikes an optimistic tone: All who heard [Christ] were astounded at his understanding (Lk 2:47).

In his final rendering, however, Hunt interprets this familiar episode as a tense confrontation between Christ and the elders.

Blindness and recognition

The Christ Child’s probing gaze cuts through the busy scene, catching the eye from every vantage point. The viewer is suddenly aware of being observed; before he begins looking at Christ, Christ is first looking at him. This device draws the viewer into the scene. It underscores Christ’s first words in Scripture, recorded in this episode: Why were you looking for me? (Lk 2:49). The spiritual life is often understood as man’s search for God. But Hunt’s Christ serves as a powerful reminder: God is always first to seek and pursue—patient, yet eager to be recognized.

Such recognition is absent among Christ’s interlocutors. The high priest—physically and spiritually blind—clings to the Old Law with palsied hands. His confrères are decked in all the trappings of traditional piety. Some sport broadened phylacteries, a practice Christ will later criticize (cf. Mt 23:5). Servants venerate the veiled Torah while Levitical musicians look on, unaware that the Child before them is the descendant of the Royal Psalmist. All appear satisfied with the sufficiency of their traditions, attached to an excessive reverence for the word of the Mosaic Law rather than its spirit.

The same spiritual malady will plague their successors. During his public ministry, Christ will draw the ire of the religious establishment by healing a blind man on the Sabbath (cf. Jn 9). This man, for now, sits waiting, begging for alms on the Temple steps.

A monumental door separates the court of the Gentiles from the Temple’s inner precincts. It bears Malachi’s prophecy: The Lord whom you seek will suddenly come to his temple. In Scripture, this promise is immediately followed by a stern warning: But who can endure the day of his coming? For he will be like a refiner’s fire…he will purify the Levites (Mal 3:1-3). The Levitical priesthood will be tested, tried, and transformed—its abuses corrected. Christ will zealously pursue this mission of reform: Ornate latticework frames a moneychanger’s table, referencing the cleansing of the Temple.

Foreshadowing the Passion

The painting’s seemingly disparate details share a unity of purpose: all portend Christ’s rejection and death at the hands of sinful men. In the courtyard, workmen scrutinize a piece of masonry; they are poised to reject the cornerstone (cf. Ps 118:22). Meanwhile, a youth waves a scarf to drive away birds, defying the Scriptural welcome extended to these creatures: The sparrow finds a home and the swallow a nest, by your altars (cf. Ps 84:3). A grain of wheat has fallen to the ground—an allusion to Christ’s sacrifice. It lies across the threshold, ready to be crushed when the Temple door swings shut. If it dies, it produces much fruit (Jn 12:24).

Only hindsight can unveil the scene in all its weighty significance. Even Mary is not yet privy to every detail of Christ’s designs. After anxiously searching for three days, she presses her Son to explain his vexing actions: Son, why have you done this to us? (Luke 2:48). In the airy distance of the Temple, a common occurrence provides a silent reply: a distressed ewe is prevented from following as her firstborn lamb is borne away for sacrifice. Christ did not thoughtlessly disregard his Mother as he pursued his Father’s business. Twenty-one years later, Mary will remember this boyhood act as a loving preparation; it will strengthen her faith amidst the worst possible circumstances. She will once more lose her Son for three days in Jerusalem, finding him at last in the temple of his glorified body.

Hunt portrays the episode in the Temple as the grand prelude to Christ’s sacred career—the overture introducing its major themes. Aware of all that will come to pass, Christ pivots away from the encircling group of elders. The die is cast. With prescient gaze and resolute firmness, he girds his loins in preparation for the great mission ahead.

Amy Giuliano

holds degrees in theology from the Angelicum in Rome

and art history from Yale.

The Finding of the Savior in the Temple, William Holman Hunt (1827–1910), Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, England. © Bridgeman Images.

Additional art commentaries