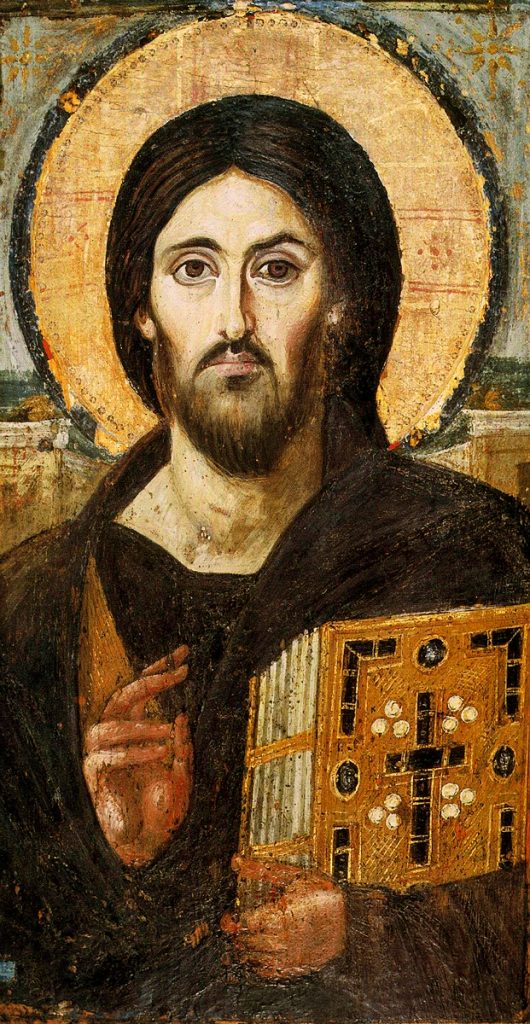

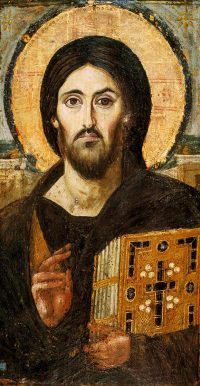

The blessing Christ, Anonymous, 6th century.

The face of God

Flanked by mainland Egypt and Saudi Arabia, the Sinai peninsula is a mountainous wilderness. Windswept, dry riverbeds carve valleys between its craggy peaks, making way for a pilgrim route—crisscrossed by Bedouin trails—to wind through the lowlands. For thousands of years, travelers have braved this desolate path to reach Jebel Musa—the mountain of Moses. Though sun-bleached by day, its broad massif of pink granite glows with fiery intensity at dawn and dusk.

This natural phenomenon vividly recalls the supernatural activity that gave the site its name: the “God-trodden” Mount Sinai.

It was here that Moses removed his sandals before the burning bush, here that he received the tablets of the Law. And it was here that a profound human longing found its earliest expression: Moses desired to gaze upon the face of God. You cannot see my face, the Lord said. I will set you in a cleft of the rock…and you may see my back; but my face may not be seen (Ex 33:20-3). Nonetheless this pining persisted, echoing within the hearts of the Chosen People and the verses of their Scriptures: Let us see your face (Ps 80:4); When shall I behold the face of God? (Ps 42:3).

Nearly fifteen hundred years after his presence graced the slopes of Sinai, God issued an unfathomable reply. “In the Incarnation,” John Paul II said, “the Eternal enters time, the Whole lies hidden in the part, God takes on a human face.” And, as if in miraculous tribute to Moses’ ancient query, the oldest extant icon of this holy face finds its home in the monastery of Saint Catherine at the base of Mount Sinai.

Surviving the centuries

The blessing Christ was likely the gift of Emperor Justinian upon his foundation of the monastery in a.d. 548. Safeguarded through the ages by the monks’ careful custody and the monastery’s imposing walls, the icon evaded a host of threats. Due to the frequency of desert raids, strict watch was kept over the comings and goings of all visitors. Until the mid-19th century, the fortified monastic structure was only accessible via basket and pulley. What’s more, the dry desert climate prevented the icon’s deterioration, and the site’s extraordinary isolation preserved it from the ravages of Byzantine iconoclasm. The 8th– and 9th-century iconoclastic waves oversaw the near total destruction of figural religious art across the empire. Sinai’s treasury, impervious to the shifting currents of the outside world, remains the only substantial link to Christianity’s earliest icons.

A masterpiece revealed

When the monastery’s inestimable patrimony was first cataloged by art historians in the 1960s, The blessing Christ emerged as the collection’s greatest masterpiece. Conservators delicately removed layers of overpainting, unveiling its original vivacity and distinctive gaze.

Christ’s imposing figure is swathed in imperial purple and situated within a shallow architectural niche. A faded red inscription identifies him as Philanthropos—the Lover of Mankind. Though likely a late-Byzantine addition to the icon, this title reflects the benevolence of his blessing gesture, while the jeweled Gospel codex in his opposite hand designates him as the Incarnate Word of God. Dark hair frames luminous flesh, focusing the viewer’s attention intensely on the face and eyes.

Double gaze

Christ’s high, convex forehead suggests wisdom; his long, slender nose and sturdy neck add an air of nobility and strength. Wide eyes contrast with small, closed lips, denoting spiritual vision and silent contemplation. Yet despite the frontality of these features, strict symmetry is absent.

The right half of the face reveals a gently sloping brow and mustache, broad cheek, and low earlobe. When mirrored, this side generates a Christ who appears meek and vulnerable. His gentle hand extends its blessing in poignant outreach towards the viewer. The left side of the face, by contrast, displays a furrowed, dramatically arched brow, which crowns a distorted eye and its off-set pupil. The dark shading and severe angle of the cheekbone clash with the steeply downturned line of the mustache, contributing to a sense of tension and disquiet. Here too, the mirrored image dramatically alters the viewer’s perception of Christ: aloof and timeless in expression, he is majestic and daunting, solemn and impassive.

The symbolic value of this duality is linked to the dogmatic pronouncements of the Council of Chalcedon. Preceding the icon’s creation by less than a century, the Council defined the hypostatic union: the fullness of divinity and humanity are united without diminishment in the Person of Jesus. The blessing Christ is perhaps the first recorded attempt to portray this paradox. The arrangement of Christ’s gesture signifies the unity of two natures in one Person, further underscoring Chalcedon’s high Christology.

The iconographic type of Christos Pantocrator—the All-Sovereign judge—became more theologically developed in the wake of iconoclasm. This title was applied to the icon in the 9thcentury, thus ascribing the additional connotation of rigor and mercy to the left and right sides of Christ’s face.

Encounter

The exceptional artistic quality of the piece derives in part from its refined application of the encaustic technique, which involves mixing pigment with melted beeswax. Illusionistic modeling of the face creates a surface palpitating with life. When viewed by candlelight, flickering shadows dance over gold leaf and waxen colors, amplifying this sense of animation.

Christ’s life-sized figure fills the frame with startling immediacy, entering the space of the beholder. In traditional iconography, no one—except Judas or demons—is ever depicted in profile, as the frontal vision of the face is considered most intimately personal. More to the point, the eyes are the locus of encounter. Indeed, it is Christ’s magnetic gaze that arrests and engages the viewer so compellingly.

The icon bears evidence of reciprocal intimacy; its lower register is worn by the hands of the faithful and tinged with the soot of their candles. A conduit of presence, a conduit of prayer, The blessing Christ stresses Christ as the image of the invisible God (Col 1:15)—the revelation of his face—the subject of Moses’ longing.

Amy Giuliano

Holds degrees in theology from the Angelicum in Rome and in art history from Yale.

The blessing Christ, Anonymous, 6th century, Monastery of Saint Catherine, Mount Sinai, Egypt. © Zev Radovan / Bridgeman Images.

Additional art commentaries