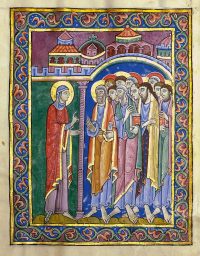

Mary Magdalene announces the Resurrection to the Apostles,

from Saint Albans Psalter (c. 1131), Anonymous.

Mary Magdalene stands in splendid isolation against a background of rich green, draped in an elegantly patterned, gold-trimmed mantle over her purple tunic, with a halo of pure gold drawing the eye to her keenly expressive face. Her gaze of earnest joy finds its complement in her upraised right hand, forming the dramatic heart of the scene: Mary Magdalene, full with what she has just seen, is preaching the risen Christ for the first time, to the gathered apostles.

An eye for beauty

This image is one of forty breathtaking full-page illuminations from the Saint Albans Psalter, made for the English anchoress Christina of Markyate around the years 1120–1130. The manuscript is a compendium of Christian prayer for liturgical and personal use, designed to be endlessly revisited by the soul longing to encounter God. The large images placed near the front of the book offer a meditative context in which to read the psalms and liturgical prayers that follow. Each image represents a major moment in the event of the Incarnation, inviting the viewer to enter contemplatively into the details of the scene and so to learn to read the whole of salvation history in each of its parts. Through an eye for beauty, the viewer receives a “memory for wonders” (cf. Ps 111:4).

An unusual Magdalene

Mary Magdalene has a host of different standard representations in Christian art, and usually they are scenes of high drama: Mary Magdalene weeping as she anoints Jesus’ feet with nard and wipes them with her hair (cf. Lk 7:36-50, associated in art with Mary Magdalene after the 6th century); Mary Magdalene throwing herself down to cling to the foot of the cross; Mary Magdalene on her knees before the risen Christ, trying to grasp the hem of his garment; Mary Magdalene bewailing her sins as a hermit alone in the desert, dressed only in her own hair or rough animal fur. The artists’ Magdalene readily topples backward with grief or hurls herself prostrate in mourning and joy; she dislikes standing still.

The Mary Magdalene of this scene is different. She stands tall and straight, radiating quiet, confident faith. Her hair is neatly tucked under her veil, not cast about in the wind of emotion. She speaks directly, without ornamentation: I have seen the Lord (Jn 20:18). The hand raised in preaching she has learned from the angel who told her that Jesus had risen, as depicted in the image on the facing page of the Psalter. This is not the Penitent Sinner or the Wild Woman so beloved of Renaissance artists: this is Mary Magdalene as the Apostle to the Apostles, whose limitless love led her to be the first to see the risen Lord and the first to preach the Truth she had encountered as having triumphed over sin and the grave.

Painted poetry

In the simplicity of Mary Magdalene’s stance, the overflowing emotions of her weeping, wailing, and rejoicing are not denied, but they are present in a subtler and richer way. Wordsworth proposed that poetry “takes its origin from emotion recalled in tranquility,” pointing to the way poetry allows a fleeting emotion, which may be only half-understood when it happens, to be grounded, explored, and better understood by being lived into more deeply over time. In this sense, the Saint Albans Psalter offers the viewer painted poetry. We see Mary Magdalene recalling the gamut of her emotions in the peace of the Gospel of the risen Christ, and through reflection on her experience, she offers the apostles more than mere emotion and more than mere experience: She speaks to them of Truth risen from the dead, aflame with the love that comes from the Holy Spirit. We who behold the image are thereby invited to enter into the interplay of emotion, reason, and love in Mary Magdalene’s preaching, recalling in the tranquility of the Holy Spirit the tumult of the Passion and the almost unbearable hope of the Resurrection, and so allowing those realities to unfold in our hearts and call us to fresh love of the Truth.

Framed by heaven

An abundantly flowering vine frames the entire image in spritely curves and vibrant colors, which do more than merely adorn the elegant border that bounds the scene. The lush vine places the events of the scene in a garden, which is at once Eden’s paradise (Gn 2:8-9), Golgotha’s horror (Jn 19:41), and heaven’s splendor (Rv 22:1-2). Memory, history, experience, emotion, tragedy, and triumph merge into the single event of Mary Magdalene preaching the Resurrection to the astonished apostles, recalled in the image’s contemplative tranquility. Still more, the flowering border reminds the beholder that everything we experience is similarly framed by the lost Garden of Eden, the all-too-familiar garden of Golgotha, and the coming garden of the New Jerusalem. The suffering and sin that make us want to collapse in grief are not isolated, private affairs. When I allow the roots of the cross to grow deep into the cracks of my heart’s hard soil, then the grace of the risen Christ springs up from the neediest places in my soul to bear fruit for the world. Mary Magdalene was the first to preach Jesus as risen from the dead, not because she was the most sinless, but because she was the first to allow her own life to be completely reframed by her longing for the Lord.

This image invites us not merely to remember Mary Magdalene’s proclamation of the Resurrection, but to participate in the forgiveness, healing, and transformation that she

received from Christ. With her, we learn how to read our own lives with a memory for wonders and an eye for God’s unfailing beauty.

Father Gabriel Torretta, O.P.

Dominican priest of the Province of Saint Joseph

and doctoral student at the University of Chicago, where he studies the history of the theology

of beauty in the Carolingian era.

Mary Magdalene announces the Resurrection to the Apostles, from Saint Albans Psalter (c. 1131), Anonymous, Cathedral Library of Hildesheim, Germany. © St Albans Psalter. Dombibliothek Hildesheim, HS St. God. 1 (Property of the Basilica of St. Godehard, Hildesheim), p.51 / Avec la collaboration de l’agence La Collection.

Additional art commentaries