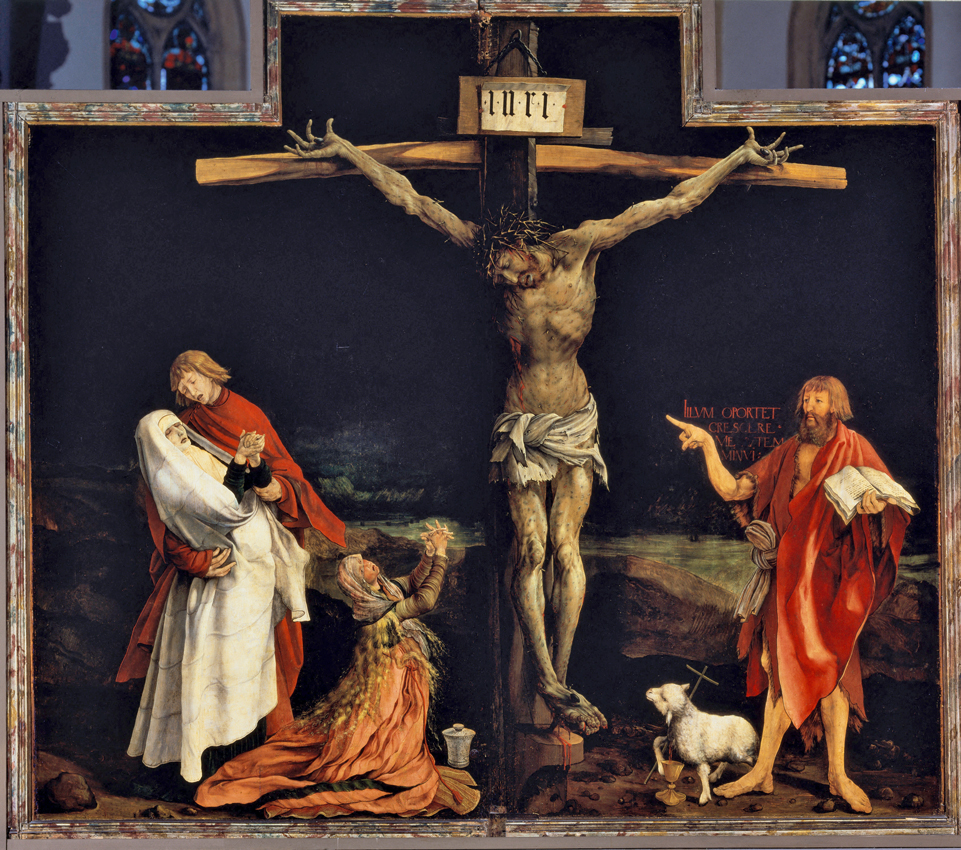

Isenheim Crucifixion (central panel, c. 1512–1516),

Matthias Grünewald (c. 1475–1528).

In the summer of 1967, a young American painter traveling through Europe stood transfixed before a painting of the Crucifixion in the Musée Unterlinden in Colmar, France. In a journal entry written on July 22, the feast of Saint Mary Magdalene, Thomas Gordon Smith describes the Isenheim Crucifixion by Matthias Grünewald in vivid detail: “Christ hangs to the right half of the painting…. His weight makes the horizontal bar bend so convincingly and the feet are nailed at the bottom…. The hollowed-out stomach and armpits, the presence of the rib cage, and all of the clearly delineated muscles of the shoulders, arms, and legs are barely held to the bone. The skin, an overall sickening yellow-green, is pocked and pricked, openings are red, of blood and muscle shown through, and are surrounded with purple, spike-driven hands which supplicate through the expressive fingers. No energy is left to support the thorn-crowned head which falls to the shoulder line. The thorns dig deeply into the shoulders.”

The nineteen-year-old art student, who would later make a career as a practitioner and professor of classical architecture and passed away in 2021, was fascinated by the symbolic power of the postures in the painting. “The cross and Christ stand so high and away from the brown, green, and black landscapes, as do the other figures. Christ should grow and I should diminish, says John the Baptist, pointing in Christ’s direction with a muscular forefinger. He wears a red, fur-lined cloak that is carelessly wrapped around his body and tied securely with a raggy sash. The changes in red hues, as the threads of the cloak pass through the convex and concave areas, are beautifully done. He wears a great brown beard and has his hair cropped off just below his ears. He is so much smaller than Christ, and yet a good deal larger than John, the Virgin, and the Magdalene. The cross faces northwest at the top, southwest at the bottom. The Magdalene kneeling at the right has glorious blond curly hair and a most expressive mouth, turned down at the corners. How the light is reflected by the crown of Christ!”

As one of Smith’s sons, I am moved to read these words and get a glimpse into my father’s thoughts and feelings as a young man. Throughout the five centuries since it was created, Grünewald’s Crucifixion has inspired and challenged countless viewers, inviting them to contemplate the brutality of the Passion and the depth of God’s love, but it is a rare opportunity to be able to “look over the shoulder” as a viewer gazes on this work of art. The painting demands our attention and invites us to reflect on what it means to see.

Behold your son; behold your mother

Two of the figures have their eyes closed, and four look with determined stares but in different directions. Jesus—whose “loving gaze freed…the adulteress and Magdalene from seeking happiness only in created things” (Prayer of Pope Francis for the Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy)—has now closed his eyes and given up the light of life through his open mouth: Father, into your hands I commend my spirit (Lk 23:46). The visible face of the Invisible Father has become—at least for now—“like the Distance/ On the look of Death” (Emily Dickinson). Like her son, the Mater Dolorosa standing by the Cross has tight-shut eyes, her clenched fingers lifted up in supplication complementing his outstretched arms. Her transfigured robes are dazzling white, as if they have already been washed in the blood of the Lamb (Rv 7:14; cf. Mk 9:3). The slant of light which she brought into the world has now departed, and her eyes—for the moment—refuse to look upon the darkness. Though her body is untouched, her heart is pierced. “Heavenly Hurt it gives us—/ We can find no scar,/ But Internal Difference—/ Where the Meanings are” (Dickinson).

John the Beloved gazes not at his departed Master, but at his newfound Mother. When Jesus saw his mother and the disciple there whom he loved, he said to his mother, “Woman, behold, your son.” Then he said to the disciple, “Behold, your mother.” And from that hour the disciple took her into his home (Jn 19:26-27). His arm tenderly but firmly wraps around her waist, expressing that from that very hour he has become the custodian of the Mother of God. Nevertheless, his downturned mouth and supplicating eyes reveal his own need for a mother’s consolation and guidance: “O thou Mother, fount of love!/ Touch my spirit from above,/ Make my heart with thine accord:/ Make me feel as thou hast felt;/ Make my soul to glow and melt/ With the love of Christ my Lord” (Stabat mater).

The strife is o’er

John the Baptist, the forerunner who has already died bravely by the headsman’s axe, looks upon Christ with the serenity of one who knows that “the strife is o’er, the battle done.” To his right, the Lamb of God gazes intently at the wounds in Christ’s feet, his front-right hoof reflecting the curve of Christ’s distended feet. Mary Magdalene is the only figure in the scene who turns her gaze to us, her upturned face and beaming arms redirecting our attention from her “glorious blond curly hair” to the One whose feet she anointed with the alabaster flask of ointment and dried with her hair.

Grünewald painted several crucifixions throughout his career—examples may be seen in Karlsruhe, Basel, and Washington, DC—but none of his other paintings approach the complexity and scale of the Isenheim Crucifixion. With shocking realism, Grünewald calls out to us: Is it nothing to you, all ye that pass by? Behold, and see if there be any sorrow like unto my sorrow (Lam 1:12). In the end, however, the painting invites us to look beyond the brutality of the Crucifixion to see the triumph that has been wrought thereby, and to cry out with confidence to the Crucified One: “Christ, when Thou shalt call me hence,/ Be Thy Mother my defense,/ Be Thy Cross my victory;/ While my body here decays,/ May my soul thy goodness praise,/ Safe in Paradise with Thee” (Stabat mater).

Father Innocent Smith, O.P.

Dominican friar of the Province of Saint Joseph and professor

at the Dominican House of Studies in Washington, DC.

His doctoral studiesfocused on medieval liturgical

and biblical manuscripts.

Isenheim Crucifixion (central panel, c. 1512–1516), Matthias Grünewald (c. 1475–1528), Colmar, France. © Artothek / La Collection.

Additional art commentaries