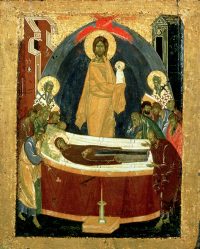

Dormition (c. 1392),

Theophanes the Greek (c. 1330/40–1405/10)

This icon of the Virgin Mary’s Dormition was produced by Theophanes the Greek around 1392. It can be admired in the Tretjakow Gallery in Moscow, next to the icon of the Holy Trinity by Theophanes’ most famous disciple, Andrei Rublev.

A unified view

Let us start by putting to rest a supposed contradiction between the Eastern and Western traditions of this mystery of the Blessed Mother, the former referring to her Dormition, or “falling asleep,” the latter emphasizing her bodily Assumption into heaven. Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerich (1774–1824) combines both traditions in her account of the event. The German mystic is said to have received detailed visions of the lives of Jesus and Mary, supporting the historicity of the Gospels at a time when an increasingly atheist culture was pushing for their mythological reinterpretation. In The Life of the Blessed Virgin Mary, she suggests that Mary, having received her last Communion from the hands of Peter, died at her home nestled in the hills of Ephesus and her soul soared into heaven (Dormition). The next day, while the apostles proceeded with the customary funeral rites, her “transfigured body” was assumed into heaven (Assumption).

The historical accuracy of icons

Icons combine a factual depiction and a liturgical vocabulary of symbols to usher us into the event in the unity of its material and spiritual dimensions. In order to enshrine and communicate this unity between the historical reality and the theological meaning, icons involve strict compositional rules that leave little room for the artist’s own inventions.

As far as the factual depiction of Mary’s death is concerned, the icon corroborates Blessed Anne Catherine’s account down to the details: Mary’s soul ascending to heaven “like a little figure,” her body “sinking back on the couch,” “her arms crossed on her breast,” surrounded by the disciples—one of them “praying at the foot of her body”—the “little altar set up by the Apostles…beside the Virgin” with “a lamp on it,” the “smoking censer” held by Peter and even the rich and “very long robe” he wore for the occasion and which nonetheless, Blessed Anne Catherine writes, “did not trail on the ground” (in the icon, Peter is clearly seen holding his robe up with his left hand).

A theological reading of the icon

If the icon codifies the Church’s memory in order to transmit it through the generations, this memory is not detached from her theological understanding of these events. Today’s tendency is to separate and even antagonize faith and reason, theology and history. But in the iconographer’s gaze, the world in its factuality is contemplated in the light of God’s providence. Things depicted relate simultaneously to a historical event and to its theological meaning. Actually, the parallels we drew between the icon and Blessed Anne Catherine’s account are far from exhausting the latter’s vivid and lengthy description of the scene. Not unlike the evangelists, the iconographer picked particular details for their theological significance. The crossed arms of Mary may depict the way her body really rested on that day, while also evoking her mystical participation in her Son’s crucifixion. The same goes for the candle lit on the altar, whose soaring, vertical light intersects with the horizontal of Mary’s remains, emphasizing the movement of her soul towards heaven. Peter holds up his richly adorned robe, lifting it up from the ground—speaking to the Church’s elevation as she is pulled upward by her Mother’s Assumption.

The mystery of the mandorla

To usher us into the mystery he contemplates, the iconographer uses, besides historical features of the scene, a liturgical, symbolic vocabulary familiar to the Church and rooted in Scripture. To the left and right of Jesus, two haloed patriarchs and two seraphim—crossing their wings above the Savior—personify heaven as it opens to welcome Mary. In the background, a darker, vertical shape extends its arches over the group of the mourning disciples. Known as a mandorla (almond), this shape is associated with the Lord’s Resurrection. It results from the intersection of two circles, making it a symbol of a reality belonging to two worlds: the glorious body of the risen Lord belongs simultaneously to the earth (as a body) and to heaven (as a glorified body). Its use in the icon of the Dormition points to Mary’s participation in the Lord’s Death and Resurrection.

In this particular depiction, however, there is also a visual continuity between the Virgin’s slightly concave body and the upper half of the mandorla, the only one visible. It is as if Mary’s body were one with the mandorla, an impression further emphasized by the use of similar hues of grey to paint the Virgin’s robe and the structure’s arches. Together, they draw around the Lord a shape we can only compare to that of an egg.

The mandorla, also called a vesica, was used in antiquity as an abstracted depiction of the womb. In Christian iconography, it becomes a symbol of the Virgin Mother’s womb as the physical and spiritual locus of the Savior. The Fathers often contemplated the double mystery of the Virgin Mary’s womb: her physical womb, in which the natural body of Jesus was formed and from which he emerged on Christmas night; and her spiritual womb—that is, her enduring faith—in which the Lord’s resurrected body was formed and from which he emerged on Easter night.

An event past and present

Theophanes the Greek immerses us in a mystery both past and present: a historical event and an event forever present, since the New Adam and the New Eve, reunited in heaven, are forever present to the Church and her members. The fruit of their love, now consumed in the heavenly Jerusalem (symbolized by the architectural visions glimpsed in the upper left and right corners of the icon), is this very Church gathered today around the Eucharist as it was back then around Mary’s couch.

Father Paul Anel

Pastor of Saint Paul and Saint Agnes in the diocese of Brooklyn, New York.

Dormition (c. 1392), Theophanes the Greek (c. 1330/40–1405/10), Tretjakow Gallery, Moscow, Russia. © Bridgeman Images.

Additional art commentaries