Adoration of the Shepherds (1485), Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449–1494).

Domenico Ghirlandaio’s exquisite Adoration of the Shepherds evokes Botticelli’s elegant style in its portrayal of the Virgin, who kneels in rapt adoration of her Son. The painting’s corniced frame announces: “Ipsum quem genuit adoravit Maria‚ (Mary worshiped the very one whom she bore). She is his Mother, yet remains his creature. In silent contemplation she considers the divine self-abasement, as he who governs the universe—now her tiny infant—kicks reflexively on the ground.

The Virgin’s face is framed with a diaphanous veil—her body shrouded by a stately mantle hemmed in gold. Though she has separated herself from her child by setting him down, his placement on her mantle underscores the intimacy of their connection. Contrasting the graceful horizontals of her hemline, a fluted column draws the viewer’s eye directly upwards from the Babe’s head towards the star of Bethlehem, partially obscured by the stable’s roof. The artist’s meaning is clear: this child can claim both an earthly and heavenly origin.

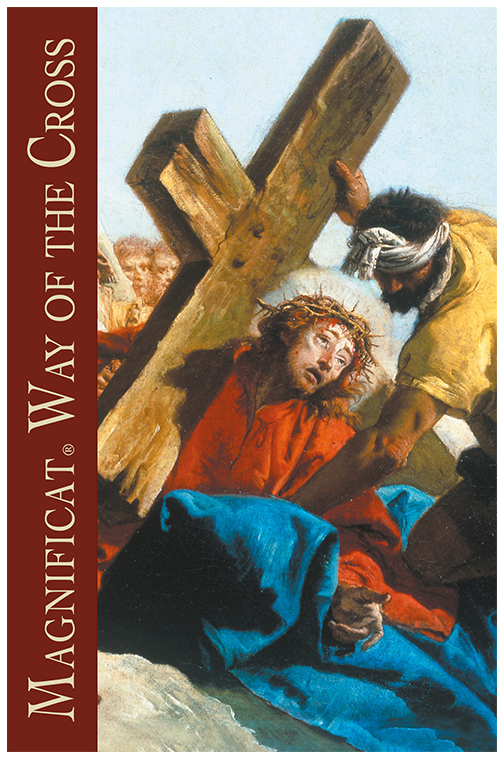

Fateful foreshadowing

Christ lies nude on the ground, not swaddled within the manger as in the Lukan account. This iconographic configuration, first popularized in 15th-century Italy, reflects the mystical visions of Saint Bridget of Sweden. The viewer is almost viscerally drawn to alleviate the infant’s cold isolation. His connection to the earth—in Latin, humus—highlights the ineffable humility of the Incarnation, while his exposed flesh underscores extraordinary vulnerability. The immutable Godhead has taken on a body capable of suffering—capable of proving love with the greatest possible potency.

Indeed, references to the Passion abound: a sarcophagus looms behind the child; before him, a goldfinch perches atop a sharply hewn stone. Christ is the cornerstone rejected by men (cf. 1 Pt 2:6-8), and goldfinches nest among thorns. Thorns and thistles (Gn 3:18) appear in a litany of hardships that befall Adam and Eve upon their banishment from Eden. Christ will be crowned with the consequences of sin—taking them upon himself willingly—as he hangs upon the cross.

Roman ruins

Rome and Jerusalem form the backdrop of the Nativity scene, dominating distant hills that fade into a bluish haze. These cities represent the successive reigns of the Hebrews and the Romans receding into history as Christianity comes to the fore. Inscriptions on the triumphal arch and sarcophagus reprise this theme. The arch fàtes General Pompey’s victory in the 63 b.c. Siege of Jerusalem, which marked the beginning of Jewish submission to Roman rule. In turn, the sarcophagus anticipates pagan submission to Christ’s definitive dominion. Its inscription relays the prophecy of a Roman slain in the same conflict: “As he fell by Pompey’s sword in Jerusalem, the augur Fulvius said, ‘The urn that covereth me shall bring forth a god.’‚

Furthermore, both arch and sarcophagus bear the cracks and corrosion of age. By situating Christ’s birth among ruins, Ghirlandaio powerfully contrasts the decaying civilization of paganism with the advent of Christianity. The old world is passing away (cf. 1 Jn 2:17), and the graves of antiquity become the birthplace of the new Redeemer.

Jews and gentiles

New believers hailing from both Jewish and pagan backgrounds—shepherds and Magi—assemble to honor the infant King. Just as the Chosen People enjoyed direct revelation from God, it is fitting that the shepherds are graced by the announcement of the angel. The Magi, by contrast, rely on natural reason—their study of the skies—to discern the divine. It is only by means of an arduous journey that they reach the fullness of truth. Nonetheless, upon arrival, both groups are equally enlightened by the rising Sun of Justice.

The annunciation to the shepherds is pictured on a hillock in the distance; a delicately gilded messenger alights above the bewildered herdsmen, the very same who have just arrived in the foreground. Their weathered faces and rustic garb contrast with the cosmopolitan finery of the Magi. Removing his woolen hat, a shepherd kneels with hands clasped in prayer, his bare knees on cold soil. Beside him, a purple iris symbolizes the royal lineage of David—who was once a shepherd boy in Bethlehem—and identifies Christ as his rightful heir.

The three kings pass directly underneath the triumphal arch—one young, one middle-aged, and one old—representing the three ages of man. Their colorful retinue moves exuberantly along the winding path to reach the Child. The idolatry of the natural world so typical of paganism is beautifully reversed: “Those who worshiped the stars are taught by a star‚ to adore Christ (Nativity Troparion). Indeed, all creation recognizes the Creator; even the ox knows its owner, and the ass his master’s crib (Is 1:3).

Liturgy

The Adoration of the Shepherds is an altarpiece—the focal point of Ghirlandaio’s larger artistic program within the surrounding chapel. While many masterpieces of the Florentine Renaissance found their way to the city’s renowned Uffizi Gallery, this work remains in situ. In fact, due to a recent restoration, the site is preserved much as it looked on Christmas day, 1485, when the chapel was consecrated.

This liturgical context unveils a layer of meaning often obscured in museums. The infant Christ is centrally positioned just above the chapel’s altar. He lies before a feed trough, cushioned by a sheaf of wheat—both unambiguous references to the Eucharist. A shepherd at his side cradles the sacrificial lamb—meant not only to be slain, but also to be eaten (Ex 12:1-28). The reverent attention of those present is wrapped in an air of Eucharistic devotion, drawing the faithful within the chapel to join in adoration. As the host is elevated at the climactic moment of the Mass, the viewer’s gaze moves seamlessly between the body pictured in the painting and the body present in the sacrament.

“The angels offer Thee a hymn; the heavens a star; the Magi, gifts; the shepherds, their wonder…and we offer Thee a Virgin Mother‚ (Byzantine Nativity Vespers). But your offering, O Christ, is unsurpassed: it is the gift of your flesh for the life of the world (cf. Jn 6:51).

Amy Giuliano

Holds degrees in theology from the Angelicum in Rome and art history from Yale

Additional art commentaries