The Calling of Saints Peter and Andrew, Federico Barocci (1535–1612).

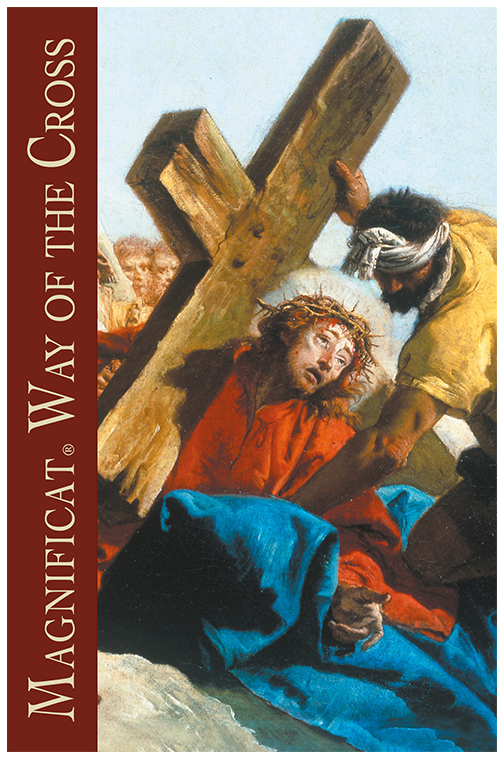

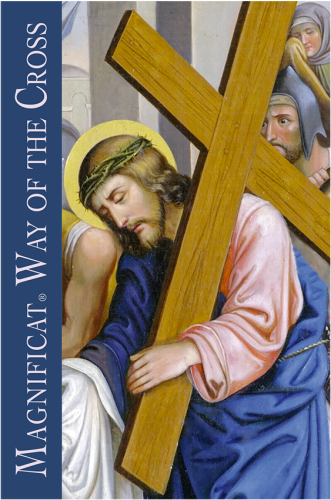

El Escorial, an austere building complex constructed by Philip II of Spain north of Madrid between 1563 and 1584, was a palace as well as a monastery, filled with relics and all sorts of religious artworks. Although it was a center of temporal authority, it was also, in the wake of the Council of Trent, a manifestation of the religious impetus of the Counter-Reformation in Spain, where the pictorial narration of the truths of the faith was launched very successfully, as it was in all of Catholic Europe. The large Calling of Saint Andrew and Saint Peter arrived at El Escorial in 1588. The Duke of Urbino, Francesco Maria della Rovere, offered the king this painting by Federico Barocci, an Italian artist who had produced between 1583 and 1586 an initial version of the same episode (now in Brussels). Barocci’s contract no doubt stipulated that he could not copy the work, because it specifies that he painted the second version from memory. They are nevertheless almost identical. The king of Spain liked The Calling of Saint Andrew and Saint Peter so much that he considered bringing Barocci to Spain: ill health and the painter’s misanthropic character reportedly prevented him from carrying out that plan, but three other pictures by Barocci subsequently joined the royal collection. It should be noted that Barocci, although little known today, was one of the most famous painters from the Marches, the region of Italy situated around Ancona, of which Urbino is a part. His rivals envied him so much that they reportedly administered poison to him, which did not kill him but permanently weakened him.

Meeting

Son of a sculptor, Barocci is in the tradition of Raphael; he combines delicate draftsmanship with a very nuanced sense of color, marked by the influence of the Venetian school. The picture in El Escorial is a perfect example. It is based on the chromatic contrast between the red of Christ’s cloak and the yellow of the tunic of the kneeling apostle; both highlighted by a paler color, they stand out against the atmospheric treatment of the background, with its shades of blue, gray, and yellow. The picture is not well preserved; the glazing sustained a lot of damage, which is a factor in the misty effect that clouds the whole landscape, but this marked sfumato technique is also a way of bringing out the scene in the foreground.

The Gospels of Mark and Matthew relate this first call soberly, with few details: As he walked by the Sea of Galilee, he saw two brothers, Simon who is called Peter and Andrew his brother, casting a net into the sea; for they were fishermen. And he said to them, “Follow me, and I will make you fishers of men.‚ Immediately they left their nets and followed him (Mt 4:18-20). Barocci added dynamism to the scene by depicting the arrival of the boat: of the three fishermen present, one has already genuflected before Jesus, while the second straddles the side of the small boat to get out, and the third has just pushed the boat ashore. All three turn their head to this prophet who preaches the coming of the Kingdom of Heaven and conversion (see Mt 4:17): the three heads are aligned on the right side of the picture, and their glances, made more dramatic by the play of shadows and by their posture, converge on Jesus. His face, crowned with a translucent halo, becomes the focal point of the composition. Barocci’s figures often have these triangular features with a thin nose, giving a profound impression of meekness, as we see here in Christ. “It has been said that meekness was the summary of all Christian virtues: it is made up especially of benevolence and patience, of friendliness and respect for all souls, and even for all creatures, since a meek person treats things meekly as he does human beings. The art of contemplating divine things is the art of being calm…. Meekness is made up of leniency and mercy, also, and a lucidity that sees human beings individually in the divine clarity, noticing only the reasons to trust and to love‚ (A Carthusian, Amour et silence). This Christ seems to show nothing but love for the kneeling man, whom he regards while lowering his eyes, with a look addressed to him alone.

Twofold call

Which apostle is it, Peter or Andrew? The title of the painting in El Escorial says “Andrew and Peter‚; the title of the picture in Brussels—“Peter and Andrew,‚ and the title of a handsome drawing in the Louvre says the same; but another drawing, preserved in Windsor, sticks with “Andrew,‚ and the first version of the painting was intended for a private chapel dedicated to Saint Andrew. The color yellow is often reserved for Peter, who is frequently depicted on his knees before Jesus, for example in the tapestries designed by Raphael for the Vatican and on the cartoons that served as their models. Now nothing in the Gospel indicates that one man preceded the other in his haste to respond to the calling, and one can choose to embrace this uncertainty so as to keep the idea of a common calling. Simon, who became the first of the apostles, cannot be dissociated from his brother Andrew, who is sometimes called the “protoclete,‚ the first to be called, because in the Gospel of John (1:36-42) he is the one to whom John the Baptist points out “the Lamb of God,‚ and then through him Simon comes to Jesus. Barocci’s picture lets the viewer see, step by step, a single movement whereby the disciples rush toward the Lord, as though they had always expected him—as if they recognized him—so as to place themselves, as the gesture of the kneeling disciple suggests, entirely at the service of the humble and meek Master. A surge of love.

Delphine Mouquin

Holds a PhD in Literature.

She is a frequent contributor to the French edition of Magnificat.

Additional art commentaries