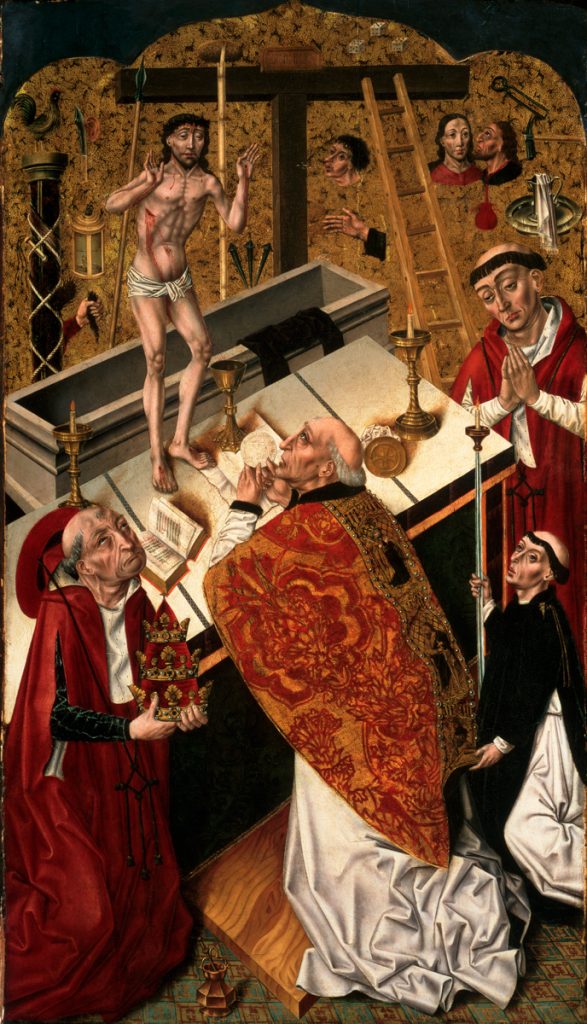

The Mass of Saint Gregory (c. 1490),

Attributed to Diego de la Cruz (fl. 1482–1500).

Jesus Christ Our Paschal Lamb

Saint Gregory the Great’s dramatic Eucharistic vision, said to have occurred while he celebrated Mass, was initially recounted in an 8th-century papal biography by Paul the Deacon, a Benedictine monk. By the 14th century, various other accounts of the beloved pope’s vision spread among the faithful. Pope Gregory’s devotion to the Eucharistic presence of Jesus also inspired artistic works such as this image, attributed to the gifted Spanish Renaissance painter Diego de la Cruz. In his dramatic depiction of the saintly pope’s vision, the sacrifice of Jesus’ Passion and death on the cross is connected to the Mass. And a unique aerial closeup perspective allows the viewer to linger over the profound vision unfolding at the altar.

Pope Gregory at prayer

Pope Gregory kneels before an altar on which rests a chalice, paten with a cross design, and sacramentary, the book of Mass prayers spoken or sung by the priest. He is vested in a papal chasuble richly embroidered with flowers, pearls, and ecclesial figures. To his left, a red-robed cardinal holds a papal tiara, a jeweled three-tiered ceremonial crown used chiefly in papal coronations and certain solemn processions. The kneeling cardinal looks heavenward, imitating the pope’s visionary gaze. An aspersorium holding holy water sits on the floor between them.

The tonsured monk on the right is an altar server who lifts the pope’s chasuble with his left hand while holding, in his right hand, a slender rod topped with a lit candle, also known as the elevation candle. These two liturgical gestures indicate the sacred moment of the Mass when the priest elevates the Host for the faithful to venerate. An elevation candle allowed the faithful to see the Host and the Chalice elevated in dimly lit churches before the advent of electricity. And the lifting of the chasuble relieved some of the weight of the priest’s vestments, allowing him to give the highest elevation to the Host. In this scene, Pope Gregory elevates a Host embossed with the cross of Jesus, leading our eye to the vision he sees over the altar.

Behold the Man

As Pope Gregory elevates the Host, a vision of Jesus as the Man of Sorrows unfolds before him. Jesus stands on the altar with one foot placed on the corporal, the cloth that holds the chalice and paten. Jesus’ feet show bloody nail marks, and his raised arms reveal more nail marks on his blood-stained hands. Pierced with a crown of thorns, Jesus’ bruised body breaks open in the wound from the lance thrust into his side. From his wounded side blood flows into the ornate chalice on the altar.

Behind the suffering figure of Jesus are several reminders of his Passion, painted against a patterned gold background. The column where Jesus was scourged is topped by a rooster, symbol of Peter’s denial. A sword and abstracted human ear recall Peter’s hasty act of cutting off the ear of the high priest’s servant. On either side of Jesus’ frame are the lance and the rod with the sponge dipped in vinegar given as drink. And Jesus’ empty tomb lies beneath the cross. Large metal nails evoke those used to crucify Jesus on the cross, on which is inscribed the letters INRI, the Latin acronym of the title given him by Pilate: “Jesus, the Nazarene, King of the Jews.”

An abstracted image of a slapping hand, a metal instrument of torture, and the face of a man spitting at Jesus are painful reminders of the mockery and ridicule he endured during his Passion. A ladder leans against the cross as we see Judas betraying Jesus with a kiss. Around Judas’ neck hangs a large red money bag, symbol of the vile greed and cowardice of his betrayal. And on the right of the painting, a tonsured monk kneels with hands folded in prayer. Above his head, a silver basin, jug of water, and towel remind us of Jesus’ humble act of service as he washed the feet of his disciples before his Passion.

Eucharist—sacrament of divine love

Pope Gregory’s vivid Eucharistic vision links the divine love revealed in the Passion of Jesus and its renewal in the Mass. As the Catechism teaches, “since Christ was about to take his departure from his own in his visible form, he wanted to give us his sacramental presence; since he was about to offer himself on the cross to save us, he wanted us to have the memorial of the love with which he loved us ‘to the end,’ even to the giving of his life. In his Eucharistic presence, he remains mysteriously in our midst as the one who loved us and gave himself up for us, and he remains under signs that express and communicate this love” (1380).

In reflecting on the gift of the Eucharist, Pope John Paul II observed that “the Church and the world have a great need of eucharistic worship. Jesus waits for us in this sacrament of love. Let us be generous with our time in going to meet him in adoration and in contemplation that is full of faith and ready to make reparation for the great faults and crimes of the world. Let our adoration never cease” (Dominicae cenae, 3).

The unique aerial perspective of this ethereal image reveals the fullness of divine incarnate crucified love revealed in the suffering that Jesus endured willingly to reconcile humanity to friendship with God. And this visual catechesis extends Jesus’ invitation to grow in union with him and love of neighbor through our participation in the gift and mystery of the Eucharist.

Jem Sullivan, Ph.D.

Teaches catechetics in the School of Theology and Religious Studies at

The Catholic University of America and is the author of Believe, Celebrate, Live, Pray:

A Weekly Retreat with the Catechism (Our Sunday Visitor).

The Mass of Saint Gregory (c. 1490), Attributed to Diego de la Cruz (fl. 1482–1500). Philadelphia Museum of Art. © Bridgeman Images.

Additional art commentaries